Tsuyoshi Ozawa: "How Can Art be a Part of Our Lives in Contemporary Society? " (#1)

Tsuyoshi Ozawa's Permanent Installations in the Province of Sanuki

Tsuyoshi Ozawa is known for his works exhibited both in Japan and overseas that acutely criticize history and society from a unique perspective with elements of reality, fiction, and humor.

Perhaps because of his diverse and complex style that does not limit his mediums to orthodox genres such as sculpture and painting, there are few opportunities to see his work in places other than exhibitions at museums and international art festivals.

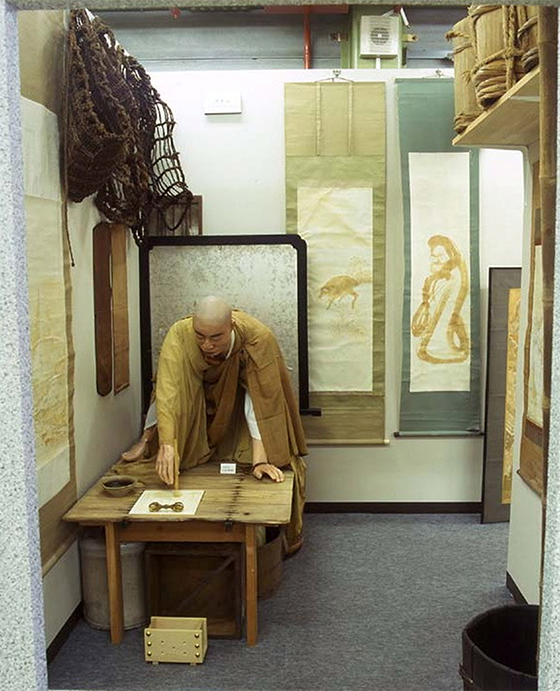

There are, however, two permanent installations of Ozawa's work in Kagawa Prefecture. One of them is The Sanuki Museum of Soy Sauce Art in the headquarters of Kamada Soy Sauce, located in Sakaide, a city close to where Kukai (774-835), the Buddhist monk and founder of the esoteric Shingon school of Buddhism, was allegedly born. The other is Slag Buddha 88 - Eighty-eight Buddha Statues Created Using Slag from Industrial Waste at Teshima which was originally created for an exhibition in Naoshima in 2006. Since 2022, the 30th anniversary year of Benesse House, the work has been newly relocated to Valley Gallery in Naoshima.

Slag Buddha 88 belongs to the context of Ozawa's "Jizoing" series, the artist's debut work and his B.A. thesis work, comprised of photographs of jizo he created and placed in landscapes while traveling to various places as a student.

Using motifs from the statues of Buddha created and located in 88 places across Naoshima during the Edo period following the "Shikoku Pilgrimage of 88 Places," and with the cooperation of local ceramic artists and students, Ozawa created statues out of slag yielded in the process of incineration of industrial waste that had been illegally dumped on Teshima.

As such, Ozawa's works are often based on research about the past and present of the places he has visited or lived, and explore ideas of nostalgia that may be forgotten in everyday landscapes, things that are uniquely developed in local areas, and the relationships between fine art and indigenous popular art, art and non-art, as well as between individuals and others or groups. What have his works originated and developed from, and in what direction will they head?

Travels, Journals, Local Landscapes, a Gentle Gaze upon People's Lives - for Jizoing

Tsuyoshi Ozawa was born in Saitama in 1965, the year after the first Tokyo Olympic Games, and grew up in a big apartment complex in the suburbs of Tokyo during Japan's period of rapid economic growth, where TV sets were rapidly becoming common among ordinary households and people were becoming gradually prosperous.

As the landscape of his hometown looked like a blend of the countryside and newly developed housing complexes as seen in Pom Poko, an animation film by Isao Takahata, the sceneries depicted in the films of Studio Ghibli look familiar and somewhat nostalgic to Ozawa as though they are his archetypal landscape.

Although Ozawa admired cartoonists, he found that he could not write stories and decided to specialize in painting upon entering Tokyo University of Fine Arts. During his days as a university student that coincided with the peak of the bubble boom of Japan (approximately 1987-1991), he discovered a catalog of the exhibition, "Japon des avant gardes 1910-1970," held at the Centre George Pompidou, Paris and learned that Japanese avant-garde art had been exhibited at art museums overseas.

Ozawa, who believed that anything new was imported from outside of Japan until then, began to inquire what was new and opened his eyes wider to the world, becoming an ardent fan of "Angura ," or the plays of the "underground theater" movement, and a frequent backpacker carrying Chikyu no Arukikata (a foreign travel guidebook series in Japan published since 1979 which became popular among young solo travelers) to foreign countries when he had time and money earned from part-time jobs.

Against the frivolous mood of society in those days, Ozawa created a coterie magazine Shirokuro [White-black] with his friends. Already at this point, he showed his dual interests that contrasted with each other, traveling alone and working with colleagues, which are both now key elements of his art.

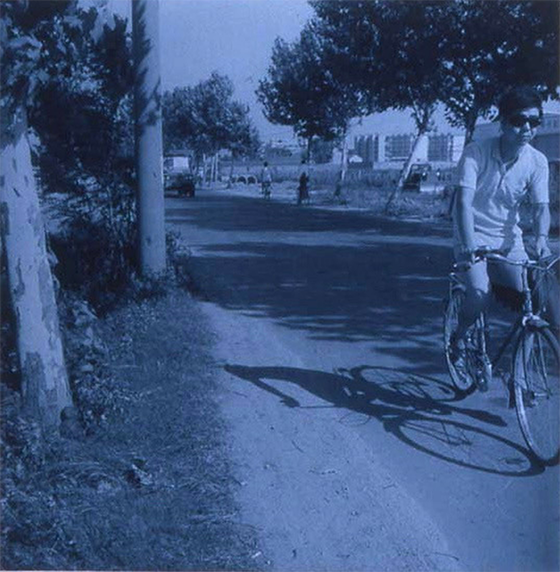

As Ozawa experienced a setback in painting back then, he was advised by his professor and contemporary artist Koji Enokura to keep a diary. Instead of texts, the artist began to take photographs everyday with his film camera. The "Jizoing" series was created from a layering of his diary, travels, and influence from Enku, a Buddhist monk he admired for carving Buddhist wood statues while traveling across Japan during the Edo period.

Interested in photography due to the resemblance of the development process to that of painting, Ozawa tinted his photographed prints in blue using blue toner as if depicting the twilight in images. To him, blue had a somewhat soothing effect, and the time at sunset, when visibility was lessened, seemed to stimulate his imagination at its peak.

He placed a small statue or a depicted image of jizo in every scene he photographed during his travels to Tiananmen Square under curfew, Panmunjeom on the border dividing the Korean Peninsula, Tehran, Tibet, Moscow, Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong, and even in Kamikuishiki where Aum Shinrikyo Cult's headquarters was located.

Initially, the artist began this series simply with a mischievous idea that he wanted to leave his trace of existence in the landscapes. As he continued photographing, he realized that any mundane place could equally become a spectacular one when sunk in dusk.

The motif of jizo, which was inspired by Enku as Ozawa has stated, quietly watches people's lives and is inseparable from possible salvation.

Between the Individual and the Collective

In addition to the "Jizoing" series derived from his solitary journey, Ozawa began the "Sodan Art" [Consultation Art ] series in 1990, in which he showed his paintings in- progress to others and revised each work as advised by them.

The concept of "Sodan Art" occurred to him when he felt tired of the excessive "me-ism" of a work of art overly charged with the ideas of an individual to the point of being unable to accept diverse interpretations. Each work in the series is entirely left to others and develops as the artist listens to what others think about the work, as if playing the game of "broken telephone." He says he thought it was interesting that there was a painting between himself and others and that conversations take place within that realm, rather than looking at a finished painting itself.

Ozawa has attempted to liberate himself from a sense of self and subjectivity, as practiced in various projects such as workshops called "The University of Sodan Art" and "Sodan Art Cafe."

In 1993, Ozawa began another important project of his early career called "Nasubi Gallery" by participating in a guerrilla-type group exhibition, "The Ginburaart," which took place for only one day on the streets of the Ginza area.

In those days, most of the galleries in the Ginza area were either rental art spaces or antique shops. Because he was skeptical about doing a solo exhibition by having to pay expensive fees in the area despite it being uncertain whether this would even lead to a breakthrough as an artist, Ozawa decided to take an alternative, sensational method by showing works of art mounted in wooden milk-delivery boxes which he substituted for exhibition spaces on the street right in front of Nabisu Gallery, a famous rental gallery in Ginza.

It was a radical project to show one artist each month with minimal costs and within the smallest exhibition space right in the middle of the most expensive neighborhood in Tokyo. However, Ozawa was not able to continue activities in Ginza because they were stopped by the police a few months later. (Since then, the "Nasubi Gallery" exhibitions took place migrating from one place to another and were often invited to other exhibitions.)

Questioning the peculiar system of galleries as rental exhibition spaces in Japan, the "Nasubi Gallery" project demonstrated a new way for the usage of space and that works of art could be exhibited anywhere without plots of land and buildings.

As for his group activities, in 1992 Ozawa participated in an art collective called "Small Village Center" that recreated art happenings and performances from the past.

Translating and combining the initial kanjis of the members' names as High Red Center (Jiro Takamatsu=high pine, Genpei Akasegawa=red brook, Natsuyuki Nakanishi=center west) did in the 1960s, Small Village Center was named after the names of its members, namely, Tsuyoshi Ozawa=small swamp, Takashi Murakami=village and Masato Nakamura=center. As its name suggests, this group aimed to reenact events of post-war art in Japan. In particular, they reenacted performances in Osaka and several other places at the suggestion of Murakami, who proposed that since they knew little about the genre, they would need to examine works by reenacting them instead of simply learning through written materials.

The activities of the group did not continue for a long period of time, but Ozawa formed another group named "Showa 40 Nenkai" (Showa Yonju Nenkai; The Group 1965), whose members, all born in Showa 40 (1965), were namely, Ozawa, Makoto Aida, Oskar Oiwa, Parco Kinoshita, Hiroyuki Matsukage, and Sumihisa Arima.

Since the member artists had quite different styles from one another, the group was a collective of individuals who did not often make collaborative works but at times held group exhibitions together. The group remains active, loosely bound together.

While their activities are parodies of ubiquitous art groups in Japan and pointed out to be influential to art collectives of younger generations that emerged afterwards, the most important characteristics of the activities of Group 1965 are themed on the social aspects of Japan's rapid growth period during which they grew up.

The aim of the aforementioned Sanuki Museum of Soy Sauce was to look back upon Japan's past through art at the end of the 20th century.

As the Japanese art scene became increasingly interested in Asia since the 90s, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, a museum dedicated to Asian modern and contemporary art, was founded in Fukuoka in 1999. The Sanuki Museum of Soy Sauce Art was exhibited in its inaugural exhibition, "The 1st Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 1999."

Depicted with soy sauce as paint that was considered most suitable to represent the perspectives of Japanese people, Ozawa's work replicated masterpieces from ancient times to post-war avant-garde age that offered critical questions about Japanese art history constituted by importing and adopting Western ideas and techniques of art since the Meiji era. In addition, by following the brushstrokes of old masters, Ozawa could experience how they had drawn paintings and also introduced their ideas into his work.

This essay was written based primarily on conversations between Tsuyoshi Ozawa and the author.

Other references:

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, Ozawa Tsuyoshi Sekai no Arukikata (Isshi Press, Ota Fine Arts), 2001.

Chiba City Museum of Art, Tsuyoshi Ozawa: Imperfection - Parallel Art History (Exhibition catalog), 2018

Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art, Tsuyoshi Ozawa: All Return:"Come back in a hundred years' time. After a hundred years you'll understand." (booklet), 2020.

Akiko MikiBenesse Art Site Naoshima International Artistic Director / Director, Naoshima New Museum of Art (Open in Spring 2025)

Former Chief and Senior curator, Palais de Tokyo (2000-2014), Co-director, Yokohama Triennale 2017 and Artistic Director of its 2011 edition among others. She was also guest curator for many large-scaled exhibitions including the ones of Japanese artists such as Nobuyoshi Araki, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Takashi Murakami at major museums in Asia and Europe as Barbican Art Gallery, Taipei Fine Art Museum, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, Mori Art Museum, Yokohama Museum of Art, and Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art.